Blended learning vs hybrid learning

Firstly, let’s deal with a matter of terminology. Blended learning and hybrid learning are overlapping and often used interchangeably, but there are important differences between the two approaches.

While blended learning integrates online and face-to-face delivery modes to design a mixed-mode learner experience across the course, with some elements delivered in person and others online, hybrid learning is more student-driven in that the learner can decide through which mode (online or face-to-face) they would like to access each and all the learning materials and sessions. In a helpful analogy, Simon Thomson likens hybrid learning to a hybrid car in that you can choose which power delivery source (electric or traditional engine) to use, depending on logistics or the journey you will take.

Jisc also highlights the greater degree of choice exercised by learners in the hybrid learning approach, a view endorsed by Roberto Prieto of EIT Digital (2021), who emphasises the irreplaceable nature of the value attributed to face-to-face learning in blended learning: “Unlike hybrid learning, blended learning does not compromise on the unique aspects of face-to-face interactions”.

The online component is challenging to deliver, however. It is important to recognise that online learning is not and can never be simply a case of transferring the traditional teaching and learning model online. Initially, under pressure created by the Covid-19 pandemic, many providers struggled with this, as they had not conceived of digital teaching and learning as a new and distinct practice, a systemic solution, which requires a different mindset and a range of skills, in the creation, management, delivery and utilisation of the courses, not generally exercised in traditional classroom teaching.

Models of blended learning

For the learner, previously accustomed in formal education and professional or work-based education to being merely the recipient of knowledge and information conveyed through the teacher or through various media, the shift to blended and hybrid learning represents a rich opportunity to moderate how, when, in what order and for how long the learning takes place. This results in a more andragogical model of learning in which the learner can be self-directed. Not all learners, however, have the necessary motivation and skills to benefit from self-directed learning. We shall explore the implications of the andragogical theory of learning below.

Positioning blended learning in a framework of learning theories

Tony Bates, a respected online education expert and experienced practitioner based in Ontario, Canada, has suggested that there is perhaps a need for a theory for blended learning. I tend to agree. Blended learning reflects the range of teaching and learning possibilities inherent in combining modes of delivery for learning, online (including mobile) and in-person, the former of which is evolving rapidly as digital technology advances.

So, does it make sense to focus so much on the mode of delivery, potentially at the expense of the objectives behind learning teaching and training? The latter include having a significant impact in the development of the individual and delivering learning outcomes which enhance knowledge and capabilities, in an engaging, co-designed learning experience. As Bates points out, good practices derive from theories being tested and put into practice; without the guidance of a theoretical framework, we are in danger of mere experimentation, which is certainly one valuable means of learning, but not sufficient by itself. Lets look at some of the blended learning theories that have emerged so far.

Complex Adaptive Blended Learning System

Wang, Han and Yang (2015) proposed a theory of the Complex Adaptive Blended Learning System comprising an ecosystem of 6 inter-related elements co-operating in a dynamic and adaptive relationship, a framework for the design of a blended learning system. The six components are as below, and each breaks down into sub-components:

- the learner (researcher, collaborator, practitioner etc)

- the teacher (facilitator, moderator etc)

- the technology (online, asynchronous, offline etc)

- the content (problem-based learning, collaborative learning etc)

- the learning support (services for learning)

- the institution (organisation, strategy, infrastructure etc).

What is interesting about this theory is that it is context-agnostic, i.e., it can be used in any context of learning, whether work or formal education. Here, there is a useful distinction between “content”, meaning learning method such as problem-based, and “technology” which is essentially the mode of delivery. This framework delineates the context for blended learning and is a useful map for designing a blended learning course.

Community of Enquiry

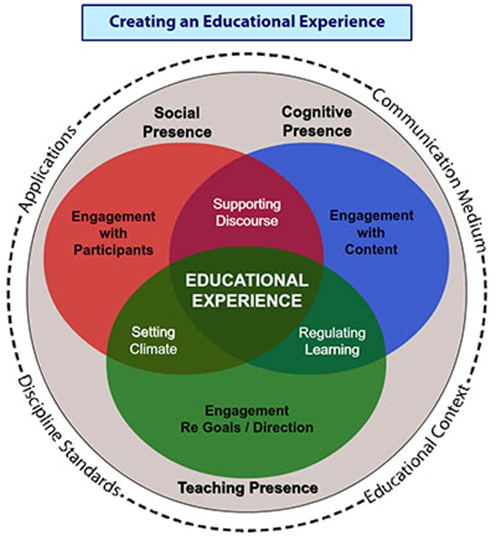

Another well-known theory for blended learning is the Community of Enquiry framework (Garrison, Anderson and Archer, 2000; Garrison 2009). This has three overlapping spheres of social, teaching and cognitive. At the heart of this theory are two key principles: firstly, that active learning is effective learning, following the theory of John Dewey and others, and secondly, that the environment in which the learning takes place is critical for the success and impact of the learning. This chimes with Laurillard’s emphasis on context.

The Community of Enquiry model and is another very useful framework for designing blended learning; it has at its core community learning and has much in common with Wenger’s community of practice models. We are after all social beings, and we make sense of the world through others’ shared experiences. Our own experiences, without comparison and sharing with others, would have little meaning.

In this theory, there are three types of key processes to be managed around the educational experience: setting the climate (teaching – social), regulating the learning (cognitive-teaching) and supporting discourse (social-cognitive). Similarly, there are three different types of engagement to stimulate and manage: engagement with the content, engagement with participants, engagement with direction/guidance. Due to this elegant and inclusive simplicity, Community of Enquiry is then also a very valuable framework for management a blended learning programme, though obviously it can be applied to many other learning initiatives too.

Figure: Community of Inquiry model (Garrison, Anderson and Archer, 2000)

Subject, Pedagogy and Modality framework

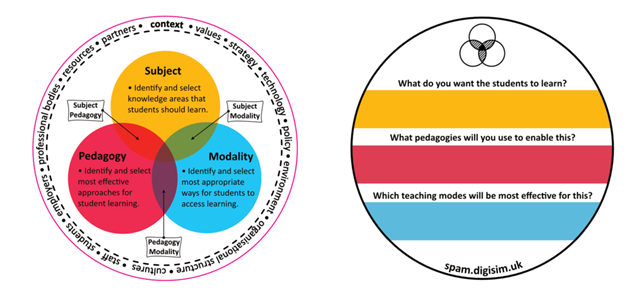

More recently, a framework for hybrid education was created by Simon Thomson (Director of Hybrid Learning, University of Manchester). The SP&M framework leans on and significantly adapts the Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK) framework proposed by Koehler and Mishra (2006).

Rather than technology, Thomson recommends modality, since the former term is rather vague and tends to encourage a technocentric approach. Thomson also prefers subject to content, as content implies resources and subject knowledge fits better with the academic perspective of teaching and learning.

The SP&M framework asks three key questions for the design of hybrid learning:

- What do you want your students to learn? (What knowledge and learning)

- What pedagogies will you use to enable this? (With which L&T methods, e.g. problem-based learning, social learning etc.)

- Which teaching modes will be most effective for this? (When and where, i.e. online, F2F, synchronous/asynchronous)

Using Thomson’s framework, the blended learning designer can identify the subject pedagogy to be used, the subject modality and the pedagogy modality. Using these overlapping domains is a powerful and elegantly simple way to view and design flexible learning provision.

SPaM Framework © 2022 by Simon Thomson (licensed under CC BY 4.0)

The SP&M model was designed for higher education, while in professional education (a fully andragogical world), the term content would probably work better than subject, teaching and learning method would be more meaningful than pedagogy, while modality or mode would remain the best term to describe the where and when of the blended model, which is why I have used it throughout these blog posts.

Pedagogy, andragogy and heutagogy

The term “pedagogy” is used in different ways across education. It is widely used to describe the art and science of teaching, and this usage has become mainstream. However this obscures the Greek origins of the word which imply teaching of young people, specifically. Post antiquity, as teaching and learning has evolved, formal education, which in centuries past was essentially the schooling of children and young people, has extended its boundaries to include adult learning of many types. In this way, one could argue that the evolution of teaching and learning has outdated the term pedagogy. Hence the use of the term andragogy, for “the art and science of helping adults to learn” (Australian VET Research Association).

The term andragogy was coined in 1833 by a German educator, Alexander Kapp, in the context of German classicism and his revival of Platonic ideals on adult education, specifically education being the formation of character including ethical and spiritual development (paideia). This educational philosophy is the basis of “bildung”, the untranslatable German concept meaning the deliberate cultivation of the holistic self for the enactment of a responsible purpose in society, including “value consciousness and critical knowledge developed in response to education” (Danner 1994). Bildung was seen by Humboldt as a personal flowering of all the individual’s abilities equally (the antithesis of the knowledge compartmentalisation and specialisation that has characterised modern academia and the professions).

These bildung-influenced aspects of andragogy have been rather neglected over the course of time, but in the 1950s US, Malcolm Knowles developed the theory of andragogy extensively into the version we know today. That said, Knowles’ theory was far closer to the bildung concept than is often recognised, echoing the former in at least three respects when describing the outcomes of adult education: “Adults should acquire the skills necessary to achieve the potentials of their personalities”; “Adults should understand the essential values in the capital of human experience”; “Adults should understand their society and should be skilful in directing social change” (quoted in infed.org).

Knowles’ most influential adult learning theory is the set of principles that underlie adult learning and have become the six defining principles of andragogy, which is self-directed learning:

(i) the need to know is the reason for adult learning;

(ii) agency of the adult learner, knowingly responsible for their own education;

(iii) experience is the basis for learning;

(iv) readiness to learn due to the relevance of the learning;

(v) problem rather than content-centred orientation to learning;

(vi) motivation to learn.

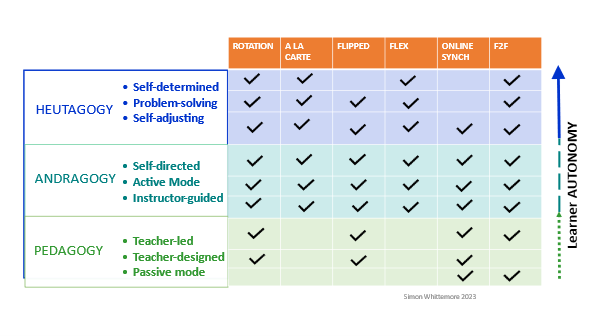

Finally, heutagogy, (Stewart Hase of Southern Cross University and Chris Kenyon, 2000) was presented as the next step in the evolution of learning: from pedagogy to andragogy to heutagogy and self-determined learning. As we can see from the diagram below, while in pedagogy learning is teacher-led, in andragogy, self-directed and instructor-guided, in heutagogy, learning is self-determined, problem-solving (and problem perceiving) as well as self-adjusting. Hase and Kenyon argue persuasively that heutagogy enables learners, and therefore both organisations and individuals, to develop the capability to cope with contemporary change and complexity. Self-determined adult learners, with well-developed problem-solving abilities, are able to apply their learning in new, unanticipated and unprecedented situations (Hase and Kenyon, 2007). In short, they develop that most vital of 21st century competencies, learning agility.

So where does blended learning fit in this hierarchy of learning theories? The answer lies in the fact that blended and hybrid learning are not theories but methodological approaches, so can be applied across and within each of the pedagogical, andragogical and heutagogical models. However, on further analysis, we can see that in practice blended learning is less compatible with both pedagogy and heutagogy, and this has implications for its application and development.

Practices associated with blended learning

For the reasons described in the first blog post in this series, blended learning in practice is difficult to pin down. However, there are several practice models commonly associated with blended learning. Primary among these is the concept of the “flipped classroom”. This term denotes the practice of inverting what is done in traditional face-to-face teaching with what is typically done in the learner’s own time, so that classroom time is used for interaction, discussion and shared reflection whereas the learner’s own time online is used for reading material or covering the traditional content. Like most of the blended learning models, the flipped classroom enhances the learning experience by switching or rotating the locus of learning.

This practice is certainly innovative and is likely to lead to a richer learning experience, making use of the diverse perspectives within the classroom (traditionally kept passive) to build on what is understood by the individual learner. The flipped classroom is compatible with andragogy as it is instructor guided, objective based and there is an element of self-direction in the personal learning time. However, we cannot describe it as heutagogy, as it is not self-determined as the content is generally decided in the provider-defined course curriculum.

Let’s consider the other key practices associated with blended learning and hybrid learning and examine how they align with andragogic and heutagogic theories,

- Rotation models, in which learners rotate between several different activities/exercises, one of which is online:

- Station rotation – learners are assigned in groups to “stations”, where they focus on one task, e.g. defining the problem or discussing alternatives using online examples then move to the next station, covering all stations equally;

- Lab rotation – learners rotate between a computer lab or similar and face-to-face learning;

- Individual rotation – individual learners rotate between online and face-to-face in a pattern that matches their learning styles and needs;

As is the case with flipped learning, rotation models switch or alternate the traditional locus of learning in a pattern and are likely to lead to greater learning agility, as they involve exploring the topic in different contexts, discussing or applying what has been learnt in one context or medium in another ( e.g., group) context.

- Flex (or Hyflex) learning – online learning is central but flexibility is the key and facilitator/teacher support is provided when needed;

- A la carte – learners can choose which activities or sessions they want to take face-to-face and which online, and they will have the support of the trainer/teacher when needed

- Enriched virtual learning (majority online) – there are some on site face to face sessions, but the majority of the learning can be done virtually.

- Enriched face-to-face learning – the majority of learning is done in person, typically in groups, but is supplemented by online materials made available.

Figure: Blended learning modes mapped to learning theories

The diagram above attempts to map blended learning practices with educational theories. The key differentiator is the degree of autonomy of the learner. As we can see, the more autonomous – or heutagogical – the learner is, up to a certain point, the more compatibility there is with these flexible blended models; practising the à la carte, flipped classroom or flex model is not compatible with traditional pedagogical models, for example.

But equally, fully self-determined learning, where adult learners set their own learning objectives, content, schedule and delivery mode, may not be fully compatible with complex blended models such as flipped or synchronised online learning, as these require a strong element of organisation/learning provider/teacher planning and delivery.

A hybrid learning approach allows more choice on the part of the learner, so in that sense it is more compatible with self-determined learning, but the learner still does not have control over the choice of learning materials, provider and content. This very simple and somewhat crude analysis shows how central the degree of learner autonomy is to the design of the blended learning solution. It also shows that Knowles’ six principles of adult learning, as encapsulated in the andragogical model, are highly compatible with blended learning practices.